Sangeet Darshan of Ram Vilas

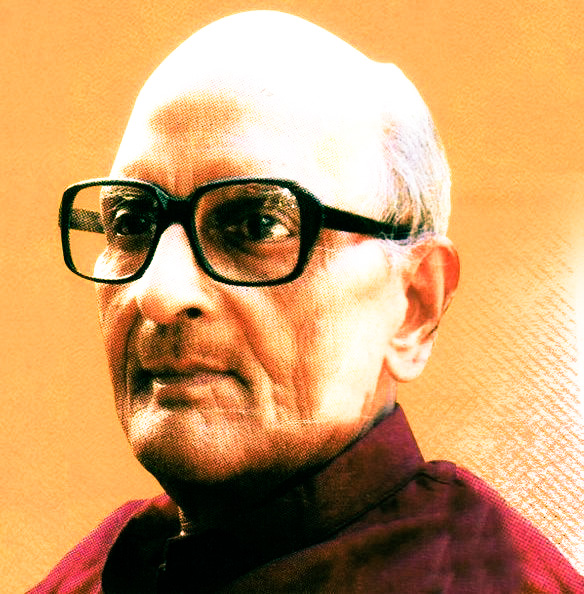

Ram Vilas Sharma has been a profound scholar, penetrating critic and thinker of our times. The honest evaluation of his long-standing work, its various aspects and aspects, will probably begin now.

His writings and his thinking have been sporadically exposed to the general reader of Hindi - sometimes reading him on the shadowy poet Nirala, and sometimes passing through new poetry and existentialism. On the one hand he was writing on Vrindavan Lal Verma, Premchand and Nagar ji, and on the other hand he was thinking very frankly on Rabindra and Sharat, the writers of Bangla. Not only was he a deep scholar of English literature, he was also interpreting the literature of Russian writers from Leo Tolstoy to Boris Pasternak. Valmiki and Bhavabhuti writing in Sanskrit and Kalidasa on the other hand seemed to investigate the value consciousnesses of characters in Greek tragedies and Shakespeare's plays.

Literature was the focus of his contemplation - but linguistics, philosophy, history, and the arts were also his subjects. Then his writing spread to the end of the country and time, this writing was not just a simple writing or a one-sided review. He was entering the world of works with his social vision and historiographical vision, something such that in the characters of literature, their expressions, their dreams, words and all the instruments, the reflection of all the tendencies of a society, an era and a period is visible. I was emerging.

By assimilating the basic consciousnesses of Marxism or dialectical historical materialism, they were moving forward by making them the basis of their thinking-analysis - even today when great stalwarts are engaged in classical debates on all this - and are criticizing, Ram Vilas He was vigorously 'applying'. But it is not that he was simplifying by adopting a theory mirroring the reality of Marxism - he has been a very careful and careful thinker. In the light of the feudal era, when he reads Kalidas or reads the feudal age in Kalidasa, he also says - "The literature of Kalidasa reflects the social system of that period, as well as a large part of it is free from that system." He also creates a fantasy world. Therefore, whatever we find in Kalidasa, we cannot consider it as the social reality of that era.

Similarly, they depict the characters of Shakespeare's tragic plays Brutus, Hamlet, Claudius, Macweth, Lady MacWeth, the daughters of King Lear and Desdimona, Iago to illuminate the dark and bright corners of Europe's Renaissance by interpreting moral sense and conflict. And it was on the basis of the philosophy of dialectics and historicism that he always looked for links in things, in arts, in phenomena. Because nothing is born completely autonomous and cut off. That is why they combine different arts, philosophies, science and economy to understand Europe's Renaissance as a whole. And Indians used to say about the Renaissance that it is not without reason that the Taj Mahal, Tulsi and Tansen are the products of the same era. He would make constant comparisons, between the East and the West, the works and people there, (Plato Aristotle with Bharata) of literature and music, philosophy and literature, folk languages and folk music, ... and then put up some establishment.

Why should it be surprising if such sensitive and inquisitive Ramvilas make non-trivial establishments about the history of music and its relation to the Renaissance. Not only music, he had a deep love for drama and painting too. His passion for music was so much that he wanted to learn singing at all costs, he also played violin and tabla. He writes - "I have decided that I want to learn music, music is as beautiful as poetry, perhaps even more beautiful. No matter how you describe the joy of poetry, find the main reasons, but the joy of music can be known only from the heart."2 Or "Every art has its medium. Every art has its own architecture, its own graphical cuisine. The medium of music is sound. The sound can evoke such sensations which are difficult to reach in other arts.

In this book written on music, Ram Vilas ji's son Vijay Mohan Sharma has also presented the hallmark of his personal collection of music. It has cassettes of legendary singers and instrumentalists of Hindustani music (Mallikarjun Mansoor, Paluskar, U. Fayaz Khan, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Bhimsen Joshi, Siddheshwari Devi, Kishori Amonkar, Ravi Shankar, Bismillah Khan, Alauddin Khan) and also Carnatic music. Along with classical music, he was also a lover of Shamshad Begum and Muhammad Rafi. He also listened to the symphony compositions of Western music with awe and started imagining landscapes of nature while listening. He was very fond of Baraw and Mendelssohn, who composed music while sitting on the beach in the north of Britain.

And the natural result of this love was that not only did he immerse himself in the experience of music, but he also continued to read, think and write about music. From childhood till the last years of his life, music remained with him. He was even trying out the theropetic role of music on himself. Those who knew him closely have also written that when he listened to music, he used to stop everything else - taking all the senses along, he used to step into the world of music with his mind and soul.

Such a mindful Ramvilas ji goes in search of the history of music from the hymns of the Angveda to the Natyashastra, the literature of Amir Khusrau and saints, Sufis and devotees and finally to the British period. in these they

Festivals and folk music, intense of folk music and languages, folk music and court music, the religious outlook and the undivided music of the Hindi caste, raise much-needed issues of the bleakness of Arabia and Iran and the British era - and sometimes from Carnatic musical traditions in comparison. On the wider panel discusses the music of the Renaissance of Europe.

The way Ram Vilas ji has brought out the sensibilities and details of pictures, dance music in the hymns of Agveda, it is very miraculous. For humanistic and realistic interpretations of the Vedas, he had to become the wrath of the so-called progressives - but when did Ram Vilas ji accept such inertia and limitations. He clearly says - "If anyone understands the Angveda as a scripture or ritual, then explain it." For me, they are a unique book of philosophical poetry.

In the similes of the hymns, in the kriyapadas or images, they begin to see glimpses of the life of the Vedic, and when they lift the veils of mystery, they see the chakras and aaras of the charioteer which is the basis of the painting and architecture - this wheel of the chariot Kalachakra Becomes, whom the poet of the gveda turns. The sun comes in hymns and covers up the darkness like a leather worker - or drowns the darkness like leather in the sea. The wonderful sense of painting awakens in the description of the Maruts sitting on black trumpets, carrying golden crowns and weapons and pouring treasures on the earth with their chariots. Ram Vilas ji says that these treasures are clouds and the wealth they shower is water. Then the dawn comes and fills not only the space and the heavens but also the earth with light and colours, opening the door to the east so that the light may come out of the darkness.

After discussing the images of dance, Ramvilas discovers twenty names of musical instruments and their references. While reading every hymn, the imagination of Ram Vilas ji also gets disturbed. They listen to instruments like the veena and the majire and find references to the seven notes. Above all, Ram Vilas ji calls the Vedic sage a 'poet' by not calling it a sage - "The poet does not remember this musical instrument (Karkari) after hearing the voice of the bird."

Similarly, Ram Vilas ji examines the Natyashastra of Bharat Muni which puts forward the Indian vision of harmony, coexistence, and samahara of the arts (natya, dance, music). He decodes the nuances of the Natyashastra as well as its origins, the Lokayatik consciousnesses of thought, and the inner-courses that flow beneath the ground. In this effort also he keeps two more representative texts of the same era at right angles. Charaka Samhita, a book on physical diseases and a book on politics, economics and social system - Kautilya's Arthashastra. He writes - "The Natyashastra, Charaka Samhita, Kautilya's Arthashastra reflect the culture of the same era. All three realists are influenced by Lokayat tradition. There is literature in one, physiology in the second and social science in the third and the purpose of all three is Lokaranjan, Lokopadesh and public-benefit. Here too he compares Bharata with the poetic and theatrical visions of Plato and Aristotle and proves that Bharata's approach to the arts is more healthy and positive and transcendental. For the plates, the poets and artists are passionate, Aristotle wants to catalyze mental feelings with drama - but Bharata wants to take the suffering humanity to the land of joy - he considers feelings not diseases - the basis of rasa. Ram Vilas ji opens the 'myths' related to Natyashastra with realistic possibilities of how 'Natas in heaven were cursed by sages and drama came to earth'. They say that these sages were actually priests of Bharata and were enraged at their ridicule and were thus placed in the natal Shudra varna. While discussing the music, Bharata discusses the 'Prakriti' of the seven swaras. Regarding the relation of rasas to music, he says - Humor and make-up ... from the abundance of Gandhara and Nishad, when there is a plurality of 'Madhya' and 'Pancham' voices come the Karun Ras. Ram Vilas ji concludes that although the word 'Shastra' is attached to 'Natyashastra', there is no such tightness in it like the scriptures. And the point of view of folk and artisan and actor has been prominent everywhere.

Whatever establishments have been laid by Ram Vilas ji about music, its land has been made by the discovery and ideas of Acharya Brihaspati. And Ram Vilas ji gives a lot to the reader of Hindi by adding his vision to it. Like in the folk music of Hungary Russia Mongolia, Acharya Brihaspati can clearly hear Indian ragas (Bhopali, Durga, Malkons, etc.) - which Ramvilas ji completes by adding pieces of his understanding of linguistics.

Obviously this folk music was created when the ancestors of the Magyar people of Hungary were our neighbours. The Magyar language belongs to the Turko-Mongol family and many linguistic elements of this family are accessible in the Dravidian family.6

Yet it is a known fact that classical ragas have their origins from vocal groups of folk music and Ram Vilas Sharma also emphasizes this point strongly. They say that as it is necessary to survey the folk languages for the historiography of a language, similarly survey of folk songs is essential for the historiography of music. With this in mind, they also offer a four-stage systematic plan. The circle of these countries will become wider.

Comparing the history of Europe and India, Ram Vilas ji says one thing of the big market that the Bhakti movement of India, religious reforms and social

लेख के प्रकार

- Log in to post comments

- 165 views